The World of Inner Anatolia

Inner Anatolia, the heartland of modern Turkey, is divided into two parts. To the east lies the Anatolian steppe, the vast, monotonous plains of Galatia, Lycaonia, and Cappadocia. The western part of the steppe was known in antiquity simply as the Axylon, the ‘treeless country’, well-suited to large-scale stock-rearing. To the west, between the steppe and the Aegean valleys, rise the rolling highlands of Phrygia, supporting a mixed economy of agriculture and animal-husbandry. These remote parts of Asia Minor are a world away from the sophisticated urban civilisations of the Mediterranean world. In antiquity, inner Anatolia was always a land of villages.

Uluören (ancient Caena, Cappadocia). Dung fuel cakes (tezek) drying in the sun.

Thanks to an astonishing abundance of Greek and Latin inscriptions on stone, mostly of the Roman Imperial and Late Antique periods, we are better informed about rural life in inner Anatolia than for any other part of the ancient world. Entire classes of ancient society, all but silent elsewhere, here speak with their own voice: shepherds with their flocks, bailiffs of the great imperial estates and ranches, vine-growers and wool-merchants. The religious life of these Anatolian villagers is known to us in extraordinary detail. The church struck deep roots here at an early date; only in the epigraphy of inner Anatolia can we trace on the ground the struggles between the orthodox church and the great heretical sects of the third to fifth centuries AD. No other part of the Mediterranean world offers anything near so rich a body of documentary evidence for rural society and religion in the first five centuries AD.

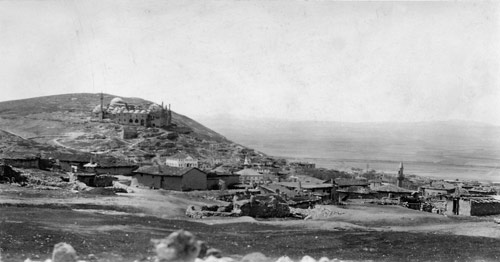

Seyit Gazi (ancient Nakoleia, Phrygia). The Tekke of Seyyid Battal Gazi, with the line of the Parthenios river in the middle distance. April 1931.

Inner Anatolia has, however, attracted remarkably little serious scholarly attention. The published inscriptions are dispersed across hundreds of obscure journals and intractable corpora; very little archaeological work has been undertaken in the region, and the barren highlands of Phrygia and Lycaonia lack an Ephesus or a Petra to attract visitors. For most historians and archaeologists, the inner-Anatolian countryside remains essentially terra incognita.

Go to a description of the MAMA XI project

Go to a description of the website and online corpus

Go directly to the monuments

Roadside picnic in Phrygia, Christopher Cox in shade under tree. 1924.

Further reading:

- P. Thonemann, ‘Asia Minor’, in A. Erskine (ed.) A Companion to Ancient History (Oxford: Blackwell, 2009), 222-235

- S. Mitchell, Anatolia. Land, Men, and Gods in Asia Minor, 2 vols (Oxford: OUP, 1993)

- T. Drew-Bear et al., Phrygian Votive Steles (Ankara: Museum of Anatolian Civilisations, 1999)

- L. Robert, A travers l’Asie Mineure. Poètes et prosateurs, monnaies grecques, voyageurs et géographie (Athens and Paris: École française d’Athènes, 1980)