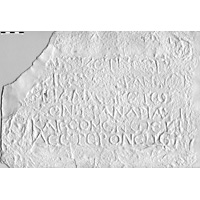

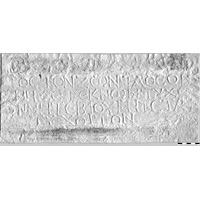

MAMA XI 40 (Eumeneia)

MAMA XI 40 (Eumeneia)

Funerary bomos of Aur. Antonia and family

- Type of monument:

- Funerary bomos.

- Location:

- Kızılcasöğüt (Eumeneia): in the garden of the mosque.

- Description:

- White crystalline marble bomos with tabula ansata, broken above.

- Dimensions:

- Ht. 0.80+; W. 0.48-0.50 (shaft), 0.58 (lower moulding); Th. 0.47 (shaft), 0.60 (lower moulding); letters 0.020-0.030.

- Record:

- Squeeze; line drawing; MB notebook copy (1956/58).

- Publication:

- None.

- Date:

- Third century AD.

[- - - - - - - - - -]

[- - - -]ς κατε[σ]-

[κεύασε]ν ἐμαυτ[ῷ]

κὲ̣ τ̣[ῇ] γ̣υνεκί μ[ου]

[- - -]

5[. ]νη κὲ τῇ [θ]υγ[ατ]-

Μ̣Η̣Λ̣Ν̣Α̣Η κὲ τῷ τ̣[υ]-

χόντι ἀνδρὶ αὐτῆ[ς]

καὶ ἐσομένῳ· εἴ τι[ς]

10δὲ ἕτερον ἐπεν-

β̣ά̣[λῃ], [ἔσ]τ̣[αι αὐτῷ]

[π]ρὸς τὸν ζῶντα Θεὸν

μηδὲ τέκνων τύχο̣[ιτ]-

ον μήτε βίου μήτε τάφ̣[ου]

15v. τύχοιτον.

...constructed (the tomb) for myself and my wife...and my daughter Aur. Anto[nia...] and whoever her husband happens to be, and their future child. If anyone inters anyone else, he shall have to reckon with the living God, nor may he meet with children, nor may he meet with life nor tomb.

In line 7, the sequence Μ̣Η̣Λ̣Ν̣Α̣Η could perhaps be read as ⟨Ἀρ⟩η̣λ̣⟨ιαν⟩ῇ. I can find no close parallels for the description of Aurelia Antonia’s potential future husband in lines 7-8 (τῷ τυχόντι ἀνδρὶ αὐτῆς); I understand the phrase to mean something like ‘her future husband, whoever he happens to be (τυχόντι)’.

The participle ἐσομένῳ in line 9 ought to refer to a potential future child of Aurelia Antonia and her hypothetical husband. In the funerary epigraphy of Asia Minor, the future participle ἐσόμενος is frequently used of anticipated children (τοῖς ἐξ αὐτῶν ἐσομένοις τέκνοις, vel sim.); see e.g. IAph2007 12.1205; I.Pessinous 153; TAM II 3, 863 (Idebessos); TAM III 1, 524 (Termessos). In a few cases, the noun is omitted: see e.g. SEG 16, 667 (Halikarnassos: ἑαυτῷ καὶ γυναικὶ καὶ τέκνοις ζῶσιν καὶ τοῖς ἐκ τούτων ἐσομένοις). In a funerary inscription from Olympos in eastern Lycia, a certain Aurelius Pigres stipulates that his tomb is intended for himself, his wife, his three sons, ‘their future wives’ (τῇ ἐσομένῃ ἑκάστου γυναικί), his future grandchildren and their own future husbands or wives (TAM II 3, 947). In an inscription from Telmessos in western Lycia, the builder of a tomb states that it is intended for himself, his wife, his children, any potential future grandchildren (τοῖς ἐκ τούτων ἐσομένοις ἐκγόνοις μου), and his son’s wife, ‘so long as she stays with him’ (ἐὰν μείνῃ μετ᾿ αὐτοῦ: TAM II 1, 53). For this final stipulation, compare (1) I.Milet VI 2, 570, discussed by Robert, Hellenica XIII, 217-8; (2) the remarkable inscription IAph2007 13.112 (shortly after AD 212: Robert, Hellenica XIII, 232), in which the odious M. Aur. Polychronios Charmides stipulates that his tomb is intended for himself and his wife Aur. Meltine, ‘so long as she remains the wife of Polychronios and so long as he, Polychronios, fathers a male child’ (ἐὰν μείνῃ γυνὴ τοῦ Πολυχρονίου καὶ ἐὰν γένηται τῷ Πολυχρονίῳ ἀρρενικὸν τέκνον: Robert, Hellenica XIII, 218); it may be relevant that a place in the tomb is also reserved for a second woman, Aur. Zosime, who seems not to be a relative of either Polychronios or Meltine.

In funerary inscriptions from Eumeneia and neighbouring cities, the right of burial was often dependent on certain stipulated conditions. In Ramsay, Phrygia II 391, no. 254 (CIG 3902m: Eumeneia, Işıklı), a certain Cassius son of Teimotheos states that his tomb is for himself and his wife Apphia and no-one else, ‘unless my daughter Apphion suffers anything before coming of age’ (χωρὶς εἰ μή τι πάθῃ ἡ θυγάτηρ μου Ἄπφιον πρὸ τῆς ἡλικίας); the assumption is that Apphion will be buried separately with her potential future husband, but if she happens to die before adulthood, she will be buried along with her parents. In MAMA XI 36 (1954/14: Eumeneia, Emircik), Aur. Alexandros reserves a place in his tomb for his daughters, ‘whichever of them dies without children’ (ἣ ἂν ἄτεκ̣νος ἐξ αὐτῶν τελε[υτ]ήσῃ); the assumption here is that his daughters will otherwise be buried separately along with their future children. Similarly, in MAMA VI 335 (Strubbe 1994: 117-8, no. 8: Akmoneia), the owner of the tomb states that it may be opened in order to inter his daughters Domna and Alexandria, ‘but if they marry, it will not be permitted to open my tomb)’ (ἐὰν δὲ γαμηθήσονται, ἐξὸν οὐκ ἔσται ἀνῦξαι). In a Christian or Jewish funerary inscription from Apameia (Ramsay, Phrygia II 537, no. 394), the tomb’s owner permits ‘the children of my blood’ (τοῖς τέκνοις ἐκ τοῦ αἵματός μου) to be buried in his tomb only so long as they are minors (ἀνενηλίκων ὄντων αὐτῶν). In two further inscriptions, one of them certainly, the other possibly from Eumeneia, family members are only permitted burial in their father’s tomb if they remain Christians (Ramsay, Phrygia II 530-1, no. 380; SEG 55, 1431).

For the curse formula in lines 11-12 (the ‘Eumeneian formula’), see the commentary to MAMA XI 36 (1954/14). In lines 14 and 15, the parasitic nu of τύχοιτον in lines 14 and 15 seems to have been particularly characteristic of the Acıpayam plain north of Kibyra: Strubbe 1997: nos. 128-37; Brixhe 1987: 34, 89. For the triple curse, on children, life and tomb (apparently unparalleled at Eumeneia), compare I.Ephesos 2304, μὴ ἐνπλήσθοιτο μήτε βίου μήτε τέκνων μήτε σώματος (Strubbe 1997: no. 33). For the phrase μήτε τάφου τύχοιτον (‘may he not receive burial’), see Feissel 1980: 471-2.

Three further inscriptions have been recorded at the village of Kızılcasöğüt: Paris 1884: 247-8, nos. 14-15 (Ramsay, Phrygia II 393, no. 266, and 394, no. 270); MAMA XI 49 (1956/57).