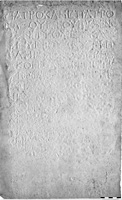

MAMA XI 45 (Eumeneia)

MAMA XI 45 (Eumeneia)

Funerary bomos of Aphia, set up by Patrokles of Eukarpia

- Type of monument:

- Funerary bomos.

- Location:

- Emircik (Eumeneia): not recorded.

- Description:

- None.

- Dimensions:

- Ht. 0.84; W. 0.36 (upper moulding), 0.28 (shaft), 0.38 (lower moulding); Th. 0.26; letters 0.016-0.020.

- Record:

- Squeeze; WMC notebook description (1954/13).

- Publication:

- Calder 1956: 49, no. 1 (BE 1958, 467; SEG 15, 810).

- Date:

- Roman imperial period.

Πατροκλῆς Πατρο-

κ̣λέους τοῦ Εὐξένο[υ]

[π]ένπτου Εὐκαρ-

π̣εὺς βουλευτὴς

5κ̣ληροῦχος τρε[ι]-

α̣κοντάρχης ἰστρ[α]-

τιώτης ἐ̣[ποί]η̣σεν

Ἀ̣φίᾳ Λ̣[- c.8-10 -]

[τ]ῇ συ[νβίῳ αὐτοῦ]

10κ̣αὶ Η[- c.9-11 -]

μνή̣[μης χάριν]

εἰ δ[έ τις ἐπιχει]-

ρ̣ήσ̣[ει - - - - - -]

- - - - - - - - - -

Line 7: [ἐπύη]σ̣εν̣ C(alder).

Line 8: Ἀ̣φια Δο̣υ̣[λί]ω̣[νος] C.

Patrokles, son of Patrokles, grandson of Euxenos, the fifth of that name, citizen of Eukarpia, councillor, klerouchos, triakontarches, soldier, made (this tomb) for Aphia... his wife, and for... in memoriam. If anyone tries...

In his 1956 publication, Calder states that the monument was seen by ‘Ballance and Calder, 1954; photograph and impression; revised by Ballance, 1956’. We have been unable to locate a photograph of the stone, nor can we find any evidence that Ballance saw the monument again in 1956. The squeeze largely confirms Calder’s readings (which appear to have been established on the basis of the squeeze, since he did not copy the inscription into his field notebook), with the exception of lines 7 and 8.

In line 2, the word [π]ένπτου was plausibly understood by Calder and by J. and L. Robert as signifying ‘the fifth of that name’; however, Koerner noted a lack of parallels for this mode of designating homonymity, and suggested that the word should be understand as the name of Patrokles’ great-grandfather, [Π]ένπτου (Koerner 1961: 60, 75).

The main point of interest in the inscription is the list of status-designations in lines 4-7. The titles of councillor (βουλευτής; Quass 1993: 382-94, and see the commentary to MAMA XI 38 [1954/17]) and soldier (ἰστρ[α]τιώτης, presumably as an auxiliary in the Roman army) are reasonably common. Far more remarkable are the two status-designations κληροῦχος and τρειακοντάρχης, both also attested in Calder 1956: 49, no.2 (SEG 15, 812: Eukarpeia, Sandıklı). It is very likely that both of these titles go back to the Hellenistic period, and reflect the existence of a Hellenistic military colony, either Seleukid or Attalid, at Eukarpeia (Cohen 1978: 46 and 79 n.37; MAMA IX xli-xlii; Cohen 1995: 299-301). Neither title is attested elsewhere in the Seleukid or Attalid kingdom, although κληροῦχοι are widely attested in Ptolemaic Egypt (Uebel 1968). However, it is certainly the case that the land associated with Seleukid colonies was regularly divided into standardised kleroi, ‘allotments’ (Cohen 1978: 45-69; Schuler 2004: 525-6; cf. Thonemann 2009). In a deed of sale from the Seleukid colony of Dura-Europos, dating to the second century BC (P.Dura 15.1-2), a property is described as lying ἐν τῆι Ἀρύββου ἐκάδι (ἑκάδι?) ἐν τῶι Κόνωνος [τοῦ δεῖνος?] κλήρωι, suggesting that kleroi at Dura were grouped together into larger units called (h)ekades (the meaning of the term is uncertain: Bikerman 1938: 161-2; Launey 1987: 51-2). It seems possible that the τρειακοντάρχης was a middle-ranking officer in the colony, with authority over a group of thirty κληροῦχοι, but in the absence of further evidence this is pure speculation.