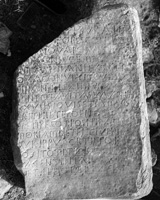

MAMA XI 72 (Sebaste)

MAMA XI 72 (Sebaste)

Latin funerary inscription of Ursina

- Type of monument:

- Funerary inscription.

- Location:

- Selçikler (Sebaste): in the cemetery.

- Description:

- White marble block, broken at top left and chipped at left, otherwise complete.

- Dimensions:

- Ht. 0.78; W. 0.54; Th. 0.26; letters 0.020-0.022.

- Record:

- Squeeze; line drawing; MB notebook copy; photograph (1955/121).

- Publication:

- Speidel 1984; (AE 1984, 849).

- Date:

- AD 390 (consular dating).

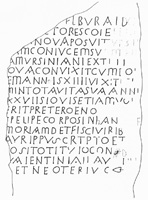

[H(anc) M(emoriam) F(aciendam) C(uravit) (?)] Fl(auius) Buraidọ

[prote]c̣tor escole peḍ[i]-

[tum] ịn ⟨q⟩ua posuit Urṣị[n]-

am coniu⟨g⟩em suam fili-

5am Ursiniani ex trib(uno) v.(?)

⟨q⟩ua convixit cum eod-

em annis XIIII vixit ẹtiạ-

m in tota vita sua anniṣ

XXVII. si ⟨q⟩uis etiam volụ-

10erit preter ⟨d⟩eno[ta]ṭạṃ s-

ẹpeli⟨r⟩e corpos in ḥanc̣ ṃe-

moriam, det fisci virib[us]

auri pp(ondera) V (quinque). scr(i)pto et dẹ-

[p]osito titu⟨l⟩o cons(ulatu) ḍ(omini) ṇ(ostri)

15Valentinian[i] Aug̣(usti) ỊỊỊỊ

et Neoteri v(iri) c(larissimi) hed.

Line 3: OVA.

Line 4: CONIUCEM.

Line 6: OVA.

Line 9: OVIS.

Line 10: OENO[. .].

Line 11: ẸPELIPE.

Line 14: TITUIO.

Flavius Buraido, protector of the schola peditum, was responsible for constructing this tomb, in which he placed his wife Ursina, daughter of Ursinianus, former tribune, who lived with him for 14 years, and who lived in her whole life for 27 years; if anyone else wishes to bury bodies in this tomb other than the woman here indicated, he will pay to the fisc 5 litres of gold. This gravestone was written and set up in the consulate of our lord Valentinianus Augustus, for the fourth time, and his excellency Neoterus.

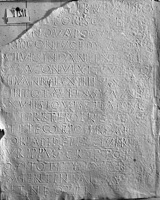

The condition of the stone had deteriorated significantly by the time it was published (from a poor photograph) by Speidel in 1984, and Ballance’s photograph and squeeze allow us to make several improvements to Speidel’s text. For comparison, Speidel’s text (AE 1984, 849) reads as follows:

[Flavi]us Buran[us]

[qui e]t Crescẹ[s] e[qu(es) de]

[co(ho)r(te)] Nova posuit Not[a]-

[tam c]oniugem suam [fil]-

5[i]am Ursiniani ex t[r](ibuno) [de co(ho)r(te)]

[N]ova. convixit cum eo p̣[l]-

[u]s m(inus) annis XIIII, ex[actis]

in tota vita sua anni[s]

XXVII. si quis etiam ṿọ[lu]-

10[e]rit preter ς (feminam) eno[tatam s]-

[e]pelire corpos in ean[d(em) me]-

moriam det fisci virib[us]

auri pp(ondera) V (quinque). scripto eṭ [de]-

[p]osito titulo cons[ulatu]

15Valentiniani A[ug(usti) IIII (quarto)]

et Neoteri v(iri) c(larissimi).

The mason seems to have known no Latin: he inscribed the letter G as C (line 4) and Q as O (lines 3, 6, 9), and confused the letters D and O (line 10), P and R (line 11), and I and L (line 14).

This inscription is one of a small number of Latin funerary inscriptions for Roman army officers from fourth-century Asia Minor: see also I.Kyzikos I 482; I.Prusias ad Hypium 101; TAM IV 1, 118 (Nikomedeia); AE 1976, 668 (Eumeneia: after c. AD 350); AE 1977, 806 (Nakoleia: AD 356); AE 2004, 1396a (Maionia: c. AD 350-75). The name Buraido (cf. ILS 2811) is apparently of Thracian origin (Detschew 1957: 80); an unusual number of fourth-century protectores seem to have originated in Illyria and the eastern Balkans (Lenski 2000: 509). The imperial nomen Flavius is a designation of rank, correctly used with an individual’s last name only (Keenan 1973-4; Cameron 1988).

The evidence for the organisation of the corps of protectores (a branch of the imperial guard) into scholae is scanty and difficult to interpret (Stein 1959: 545-6; Jones 1964: II 636-7, III 195-6; Diesner, RE Suppl. XI [1969] cols. 1113-23, s.v. protectores). That the protectores were originally organised into a single schola seems to be the implication of an undated funerary inscription for a protector from Kyzikos in Bithynia (ILS 2783; I.Kyzikos I 482): Fl. Marcus protector... militavit in scola protectorum annis quinque. Cod. Theod. 6.24.3 seems to imply that there was still only a single schola protectorum domesticorum in AD 364 (cf. Cod. Theod. 6.24.1, 10; 6.25.1). The subsequent division of this single schola into separate scholae (protectorum) seniorum and iuniorum is attested by an inscription of uncertain date from Fanum Fortunae (ILS 9204): Fl. Concordius protector divinorum laterum et prepositus iuniorum. Finally, a funerary monument from Philippi (AE 1939, 45; AE 2001, 1787a) was set up by a protector de scole seniore peditum (i.e. schola peditum seniorum), implying a fourfold division of scholae peditum/equitum seniorum/iuniorum. This last text is dated to the first half of the fourth century by Drew-Bear 1977: 269-70, on very fragile grounds (suggesting that the protector’s name, Licinianus, may derive from that of the emperor Valerius Licinianus Licinius). Bartels 2002: 711 more plausibly dates it to the fifth century, following Frank 1969: 39-40 (who misunderstands the text: it was the protector’s son, not the protector himself, who died at the age of four).

In the course of the fourth century, many Roman military regiments were divided into separate units of iuniores and seniores. It was previously believed that the earliest such divisions occurred in AD 364, with the ‘senior’ regiments going west with the senior Augustus (Valentinian I), the ‘junior’ regiments going east with the junior Augustus (Valens) (Hoffmann 1969-70: I 117-30; Tomlin 1972). However, a unit of Cornuti seniores is attested in the eastern part of the empire (at Nakoleia in Phrygia) in an inscription dated to AD 356, undermining this view of both the date and nature of the division between seniores and iuniores (Drew-Bear 1977: 267-74; Barlow and Brennan 2001: 238-42; Scharf 2005: 221-5; Drew-Bear and Zuckerman 2004: 421-2). It is more likely that the terms seniores and iuniores reflected the creation of ‘daughter’ units by conscription around a core of soldiers drawn from the parent regiment (Tomlin 1972: 261-5; Drew-Bear 1977: 270-2), a process which continued throughout the latter half of the fourth century.

The Sebaste inscription, firmly dated as it is to AD 390, is thus an important piece of evidence for the development of the scholae protectorum. To all appearances, the schola to which Buraido belonged was simply called the schola peditum (lines 2-3), although it is conceivable that a longer name should be restored here in abbreviated form, e.g. escole peḍ[(itum) / iun(iorum) or sen(iorum)]. For the spelling escole (=scholae) compare CIL VI 31971, pri(micerius) escole secundae (and cf. CIL VI 32965, iscola).

The former tribune Ursinianus, father of Buraido’s wife Ursina, is attested in another inscription from Sebaste (SEG 6, 187: Selçikler) as a member of the cohors Stablesianorum, who were presumably stationed at or near Sebaste in the last two decades of the fourth century (Speidel 1984: 387-9).