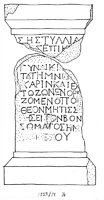

MAMA XI 142 (Pentapolis)

MAMA XI 142 (Pentapolis)

Funerary bomos of Sestullianos and his wife

- Type of monument:

- Funerary bomos.

- Location:

- Menteş (Pentapolis): in a lane.

- Description:

- Limestone bomos, broken in two.

- Dimensions:

- Fragment a: Ht. 0.45+; W. 0.63 (upper moulding), 0.50 (shaft); Th. 0.43 (upper moulding), 0.35 (shaft). Fragment b: Ht. 0.92+; W. 0.50 (shaft), 0.56 (lower moulding); Th. 0.34 (shaft), 0.36 (lower moulding); letters 0.040-0.055.

- Record:

- Squeeze; drawing; MB notebook copy; photograph (1955/75).

- Publication:

- Ramsay, Phrygia II 734, no. 661 (b only).

- Date:

- Second or third century AD.

Σηστυλλια-a

[νὸ]ς Ἐπικτ̣[ή]-

[του - - - - - -]

γ̣υ̣να̣ικὶ [γλυκυ]-b

5τάτῃ μνή̣μ̣[ης]

χάριν καὶ ἑα̣[υ]-

τῷ ζῶν· ἐνορκ[ί]-

ζομέ σ̣ο⟨ι⟩ τὸν̣

θεὸν μή τις συ̣-

10λ̣ήσει τύ̣νβον

σώ̣μα̣τ̣ος ἡμ̣-

ετ̣έρου.

Lines 6-7: ἑ[αυ]|τῷ R(amsay).

Line 8: ΖΟΜΕΝ̣ΟΠΟΝ lapis; ἐνορκ[ι]|ζόμενο⟨ι τ⟩ὸν R.

Lines 9-10: σ[κυ]|λήσει R.

Sestullianos, son of Epiktetos, (built this tomb) for ..., his beloved wife, in memoriam, and for himself, while still living; I call (the) god to witness, that nobody plunders the tomb of our bodies.

The lower half of this stone was seen by Ramsay at Menteş in 1891. The accuracy of his copy is confirmed by Ballance’s photograph; in lines 10-12, a few letters read by Ramsay are no longer legible. In line 3, probably the name of Sestullianos’ wife alone is missing: for the word order here, compare MAMA IX 118a, 129, 145, 406 (Aizanoi); Körte 1900: 427, no. 44 (Dorylaion); MAMA VII 274 (Piribeyli).

The name Sestullianos (a patronymic formation from the rare Italian gentilician Sestullius) was also carried by a mint magistrate at Stektorion in AD 161/2, Fl. Sestullianos (Φλ. Σηστυλ(λ)ιανοῦ). Six different types are known: see RPC IV (http://rpc.ashmus.ox.ac.uk) 2161, 2166, 2194, 2265-6, 3009; Robert, Hellenica XI/XII, 57-8. If the two men are identical (which is by no means certain), our inscription would date to the last third of the second century AD. Numerous Sestullii are attested in Phrygia during the Roman imperial period, all of whom can ultimately be traced back to a senatorial family of the mid-first century BC, who are known to have had financial interests at Akmoneia, just north of Stektorion (Mitchell 1979b; Badian 1980; Drew-Bear 1980b: 179-82; I.Varsovie 19. Sestullianos’ father’s name, Ἐπίκτητος, is also attested at Stektorion in Ramsay, Phrygia II 705, no. 642 (Menteş).

The reading in line 8 is not quite certain; in the fifth letter space we appear to have a nu lightly corrected to a sigma. Ramsay interpreted the clause as ἐνορκ[ι]|ζόμενο⟨ι τ⟩ὸν |θεόν, but the present participle would be hard to explain. Hence I interpret the sequence of letters as ἐνορκ[ί]|ζομέ σ̣ο⟨ι τ⟩ὸν̣ |θεὸν: compare IG IX 12 4, 1556 (Kephallenia), ἐνορκίσζομαί σοι τὸν Σεβάσστιον ὅρκιον; SEG 54, 1344 (Hierapolis), ἐνορκίζομαί σοι τὸν Θεὸν τὸν κτίσαντα τὴν γῆν και τοὺς οὐράνους, ἐνορκίζομαί σοι τοὺς ἀγγέλους Χερουβειν, κτλ. At the end of the line 9, there is only space for a single letter, and hence the reading συ̣|λ̣ήσει (rather than Ramsay’s preferred σ[κυ]|λήσει; cf. Robert, OMS V 727-8 n.7) is certain. For the phraseology, compare TAM V 1, 743 (Julia Gordos: II AD), ὃς ἂν τύνβον ἐμὸν συλήσει χωρὶς μητρὸςκαὶ γυνεκός; I.Heraclea Pontica 12, ὃς ἂν τοῦτο τὸ ἔργον συλήσῃ, σεσυλημένος ἐξαπόλοιτο.

The religious affiliations of Sestullianos and his wife cannot be established with certainty. Funerary invocations with ἐνορκίζεσθαι and ἐνορκοῦν were used by Jews, Christians, and pagans (Feissel 1980: 464-5; cf. Robert, Hellenica XIII, 101-2). For a Jewish example from Lykaonia, see IJO II, 226 (Konya): ἐνορκιζόμ[ε]θ[α] τὸν παντ[ο]κράτορα θ(εό)ν). Pagan instances are known from Diokaisareia (MAMA III 77: ἐνορκίζομεν τοὺς οὐρανίους θεοὺς καὶ τοὺς καταχθονίους), and from several cities in Lykaonia (e.g. I.Konya 125 [MAMA VIII 234a, Savatra], ἐνορκῶ τρὶς θ΄ Μῆνας ἀνεπιλύτους μηδένα ἕτερον ἐπεισενεχθῆναι, with the further bibliography cited in the commentary to MAMA XI 319 (1956/160) [Perta]).

An important local parallel instance is furnished by a funerary doorstone from the neighbouring city of Brouzos (Karasandıklı: Ramsay, Phrygia II 700, no. 635; Waelkens 1986: 185-6, no. 463), ἐνορκιζόμεθα δὲ τὸ μέγεθος τοῦ θεοῦ καὶ τοὺς καταχθονίους δαίμονας μηδένα ἀδικῆσαι τὸ μνημῖον. Ramsay fancifully attributed this inscription to a Christian ‘not fully emancipated from his old religious ideas’ or to a ‘philosophic pagan in the late third century, when Christianity had produced a strong effect on pagan sentiment’; Waelkens, who dated the Brouzos monument to the second quarter of the second century AD on stylistic grounds, more plausibly argued that it was of pagan origin, ‘but possibly influenced by Jewish or Christian formulae’ (cf. Robert, Hellenica XI/XII, 405-6).